|

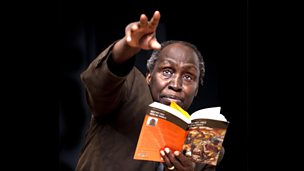

| Ngugi WaThiongo (Photo Credit: BBC) |

Book: Indigenous Language Creation

Author: Arthur TP Makanda

Publisher: African Institute for Culture, Peace and Tolerance Studies (2013)

The keynote medium of culture is language. Legacy, knowledge, beliefs, ideas, values, art, customs and tradition are assigned, packaged, encoded, fortified, updated, adapted, accessed transposed and fermented in the dynamic repositories of the tongue.

Accordingly, the position of English and French as the foremost facilities of expression in literature and other major domains of African life has been an object of controversy for generations.

Foreign languages run a cosmopolitan function as barrier-busting mechanisms for Africa’s heterogeneously branched linguistic map. Even in Zimbabwe, English is an amplified megaphone where writers can reach varied ethnicities which they would otherwise miss given the choice of one dialect.

Notwithstanding, a coterie of Pan-African firebrands, chiefly Obiajunwa Wali, Chinweizu Ibekwe and Ngugi WaThiongo contend that local languages must equate, if not supplant the virtual monopoly of adopted languages.

Zimbabwean academic Dr Arthur TP Makanda has dropped a fresh gauntlet in the bonfire with his latest book, “Indigenous Language Creation: Struggles over Policy Implementation in Post-colonial Zimbabwe.”

Makanda, an aide-de-camp to the President, scholar, war veteran and assistant commissioner in the Zimbabwe Republic Police has published extensively on the language question in peer-reviewed and international journals.

Published in February this year, “Indigenous Language Creation” argues for the need to implement policies that elevate indigenous African languages in Zimbabwe to official status, in letter and practice, a feat half achieved by ratification of a home-grown constitution on 16 March,

The constitution adopted as Zimbabwe’s official languages, Chewa, Chibarwe, English, Kalanga, Koisan, Nambya, Ndau, Ndebele, Shangani, Shona, sign language, Sotho, Tonga, Tswana, Venda and Xhosa when the ink had barely dried on Makanda’s book.

However, entering into force the new provision remains a mammoth assignment considering that home languages, with the nominal exception of Shona and Ndebele, have been languishing in obscurity and oblivion from time immemorial, with English commanding a monopoly in economic, educational and other major spaces.

It is pertinent, from the outset, to draw a snap anatomy on the enormity and complexity of the language question as it has been grappled with in literary circles.

Ngugi, easily the most militant proponent of the need to situate African languages to the same reach and authority as foreign languages, said in a recent BBC Hard Talk interview that all languages are equally important human creations.

A political system of oppression and aggression, Ngugi protests, imposed the existing hierarchy of power relations between languages.

“English is not an African language, full stop! One can say we adapt it and so on. In Nigeria, there is Yoruba, there is Igbo; in Kenya there is Gikuyu, there is Luo. We have genuine African languages,” Ngugi said.

Ngugi, who has since shunned English for Gikuyu in his writings, could not be drawn into a conciliatory mood, even when the he was presented with the possibility for Anglophone authors to deanglicise English and superimpose it with the African experience.

Contemporary Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s standpoint: “English is mine. I have taken ownership of English,” was cited as a manifesto of the alternative decolonisation of the mind.

A far from pacified Ngugi said, without understating what Adichie and his own son Mukoma waNgugi do with English, its African exponents are not decolonised but rather a part of a metaphysical empire which is unconsciously contributing to the expansion and deepening of foreign languages at the expense of their own languages.

Eminently juxtaposed to Ngugi is Chinua Achebe in Morning Yet on Creation Day: “But for me there is no other choice. I have been given the language and I intend to use it.”

“The price a world language must be prepared to pay is submission to many different kinds of use,” Achebe wrote.

Peter Vakunta takes issue with Ngugi, arguing that the latter’s position is a logocentric approach that puts a premium on the wrapping not the content.

“Hasn’t he garnered enough notoriety as a dissent writer? I believe that Ngugi wants to be heard in the dissident tone of voice for which he is already notorious,” Vakunta takes a rather hard knock on Ngugi.

Wole Soyinka subconsciously wades into the debate when he says calling Achebe the father of African literature is as ridiculous as calling Soyinka the father of contemporary African drama, Mazisi Kunene father of African epic poetry, or Kofi Awoonor father of African poetry.

Soyinka considers it a historical absurdity to ignore Zulu, Xhosa, Ewe, Lusophone, Francophone authors who were established in their own spheres before Achebe, adding that education is lacking in those who pontificate such tags.

“It legitimizes their ignorance, their parlous knowledge, enables them to circumscribe, then adopt a patronizing approach to African literatures and creativity,” Soyinka said in reference to foreign patrons of African literature in English.

“Backed by centuries of their own recorded literary history, they assume the condescending posture of midwiving an infant entity. It is all rather depressing,” he told Sahara Reporters.

The education earlier hinted by Soyinka is not the mainstream division of learning, which most Africans are familiar with, but indigenous knowledge.

Africans are, ironically, better versed with literature in foreign languages than their own which are regarded as second fiddle, hence the erroneous ascription of the title “father of African literature” to Achebe.

Why then it is still disingenous to rubbish English noting its benefit as a ready vehicle for accessing a global audience.

Of course, if Ngugi was to say his opinions in Gikuyu rather than English, they would only provoke rather limited deliberation of the problem, hence the danger of underestimating the language.

From the foregoing, the language question is clearly in the grip of a myriad complexities and Dr Makanda probes, debunks and prescribes around the octopine layers shrouding the debate with remarkable intellectual rigour.

“Indigenous Language Creation” observes the mortal danger in discarding overboard all the didactic, ideological, moral, communal and artistic codes which inhere in the home languages to pacify the wave of globalisation.

Native languages, which ceded their space to colonial languages as part of the imperial conquest, must be streamlined to greater relevance.

“The colonial view that African languages are degrading and that they are of an inferior quality is upheld,” Dr Makanda gives a progress report of what he gleaned from his field tour.

“This fact is worrying considering that some of these people, who lack self-confidence, will occupy influential positions. This prevents the implementation of a language policy based on the language creating capabilities of the African people,” Dr Makanda observes.

Dr Makanda’s departure-point from the hardwired school of home language exponents is his acknowledgement of the indispensable value of English in a cross-fertilising exchange with the home languages.

The imperative involves not only creating more space for the languages but systematically intellectualising them to make the grade in domains where English has been constantly upgraded to keep pace with the times, hence adapting needful relics from E

Dr Makanda also advances as urgent the need to promote African languages as media of instruction in schools and business. He argues that the ideal modernisation and development is inseparable from the recognition of cultures and languages of the African masses.

“The earlier we embark on the project of developing and empowering these languages,” Makanda concurs with Prah, “the better are the prospects of advancement.”

Makanda notes that American and British universities offer English courses for specific courses in an effort to develop the language. Policy planners outline development and research goals specific to occupational and academic contexts, hence branches such as business, medicine, science and technology.

The domain-specific stratification of English in its home-grounds shows that its constant development and expansion is not linear by default but by design, something possible for local languages given the adoption of similar strategies by the Government and stakeholders.

Makanda concurs with Mazrui and Chimhundu that a country cannot prosper using foreign languages without the danger of subordinating its citizens. This may appear overstretched but when one considers how infinitely inferior African feel about themselves and resort to imitation as a way of measuring up.

Mega-church founding leader Apostle Taonga Wutabwashe hints the enormity of the complex to the point where affluent people are referred to as white as though blacks cannot be affluent. Indigenous languages have been confined to spheres outside

Responses as to what needs to be done to improve the status and function of the local languages chiefly revolved around the need to utilise the public media. People suggested introducing more television and radio programmes in indigenous language.

In this respect the recent announcement by Information and Publicity Minister Professor Jonathan Moyo that 75% local programming is set to bounce back is a positive step in the right direction as far as the promotion of indigenous languages is concerned.

Respondent also suggested that indigenous languages must be made compulsory for secondary and tertiary education.

Such a move is clearly poised to be a hard sell considering the stooping feeling most Zimbabweans have in respect to local languages. Being educated is associated with thumbing your nose on your background and acting Western.

The success of the model also requires breaking the current impasse whereby students from different lingual backgrounds cannot communicate to each other without necessarily reverting to English.

It is ironic that Zimbabweans for all their sophistication cannot dialogue among themselves without recourse to an adopted medium. If students are not keen on learning their own languges beyond a basic appraisal and colloquial appreciation what are the odds that they will flourish in other local languages for the promotion of dialogue.

Perhaps, the confinement of the languages to non-key domains makes them unattractive to their supposed custodians. A Kenyan delegate to the Zimbabwe International Book Fair said: “You tell me to go back to culture. Will culture fill my stomach?” to which Ghanaian poet Atukweyi Okayi was quick to interject in a booming voice: “You! You need to be imprisoned!”

This demonstrates the need for the anticipated linguistic revolt to streamline economic and global relevance for a place in the constantly changing world.

On the whole, Makanda advocates for the popularisation and intellectualisation of home languages through and in culture, music, socialisation, economy, technical and scientific debate, advertisements and politics. The work is long overdue and all citizens and stakeholders are on call to get contribute their quota.